Alice Mary Brodie as a young woman

Aunt Alice Brodie was, it seems, our dark family secret. I remember reading a letter from my grandmother’s cousin Douglas asking my mother if she knew anything about his father’s sister Alice. My mother knew nothing, since my grandmother had never talked about her. It seems unlikely that either of the cousins had ever been told about their Aunt Alice, even though Douglas was 10 and my grandmother 13 when Alice died. It is clear Douglas, at least, had no knowledge of her. In his letter to my mother he recalls meeting an “Aunt Alice” in Egypt in 1911 and wonders if this might have been his father’s sister? I now know that it was not.

I started to uncover Alice’s tragic story quite by chance. I was on a research trip to Leicester looking into the life of my great-grandfather John Buchan Brodie. It was towards the end of the day and, on my way out of town, I stopped at Welford Road Cemetery to try to find John’s grave. Welford Road is well documented and, after a little searching, I came upon it.

Alice and Mary’s grave in Welford Cemetary, Leicester

The marble cross had been broken off and laid against the base but John’s details were clearly inscribed on the side. And then I realised there was more. On the front, worn, but still clearly legible, were memorials to both John’s mother, Mary, and his sister Alice. It was an exciting moment as I had not been able to find a birth record for Mary, and had found no trace of Alice beyond the 1891 Census. Then I realised that Alice had been just 44 when she died and I became curious as to what had happened. I resolved to get her death certificate to find out, expecting the sadness of a relatively young woman struck down by illness or fatally injured in an accident. What the certificate revealed was much more shocking.

Alice Mary Brodie had died in the Leicestershire and Rutland Lunatic Asylum, as a result of epilepsy. I tried to comprehend what this meant. In Victorian England, epilepsy was associated with mental and moral weakness, sometimes even demon possession. Patients were locked away by a society who thought it was contagious and by families concerned to protect their reputations. Alice had died in the Asylum, but how long had she been there and was she committed because of her epilepsy or was there more to it?

The Alice I knew to that point was a well-loved daughter and sister. She was born in Mhow, India in 1868, fourth-born child of William John Brodie and Mary Oldfield Wise Brodie, and named for her sister, who had died of convulsions aged 15 months, less than a year before. The safe arrival of this new, apparently healthy, daughter must have brought relief and comfort to her parents and excitement to her older siblings, Bessie, aged seven, and John, aged five. The year had started well for the family with William being promoted through the ranks to QuarterMaster Sergeant, responsible for supplies and stores of the Regiment. Such a responsible position would have led to improved living conditions for the family, as well as a “behind the lines” situation. Having been in battle 10 years earlier in the Indian Rebellion, this must have been a welcome development for both William and his wife.

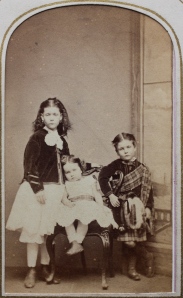

But their time in India was drawing to a close. In 1870, William’s regiment, the 95th Foot, returned to England and the 1871 census shows the family living in the new army barracks in Alverstoke in Hampshire. An engaging photograph of the children around this time shows toddler Alice, wearing a tartan sash and leaning against her older sister, with her brother, in full Scottish dress, on her other side. The Brodies were always mindful of their Scottish heritage!

In December 1873, William transferred out of the 95th Foot to the Leicestershire Militia and the family moved to Leicester, where their younger son, and last child, Harry, was born in 1875. It seems that the family were comfortably off at that time, certainly with enough disposable income to have regular family portraits taken. The resulting pictures are poignant and charming: we have Alice, aged about five, with her mother and what appears to be her dog; Alice a few years later, as a young girl, looking very smart in her first solo portrait and a couple of Alice in her late teens, with a solemn, distant expression, typical of photography at a time when exposures were long and sitters had to stay very still.

A hint of possible ill health comes in a letter from her mother to her aunt, dated 1880, in which Mary reports that “dear Alice is in much better health”, suggesting that she had not always been so. But otherwise the family appear from all evidence to be happy and relatively successful, with no shadows of what was to come.

In 1885, life changed completely for Alice and her family. Apparently without warning or explanation, Alice’s father abandoned his family and left the country to go to America. We can only speculate on the reasons why he left as he did. Family lore suggests that he may have had a drink problem and that he had always been an unreliable scoundrel. But this seems to be largely based on the report of his younger son, understandably angry at being abandoned by his father at the age of 10, and is hard to reconcile with what we know of him prior to his leaving.

William spent 21 years in the army and, although he was disciplined on two occasions for minor (drink-related?) offences, he also received five good conduct awards and was eventually promoted to one of the highest non-commissioned officer positions in the regiment. After retiring from the army, he became book-keeper to the cutlery manufacturer Tomlin and Sons and, on leaving after only three years service, he was given an ornate silver-plated platter, which I still have, engraved to him as “a mark of esteem and respect”.

He went on to manage the Leicestershire Institute for the Blind shop and workshops in Granby Street. This was a live-in post so it is possible that, by this point, he was already estranged from his family. When he left there, in 1885, possibly just weeks before leaving the country, his colleagues presented him with a leather album “… for his great kindness and urbanity to all during his three years’ residence as manager…” While these could be simply social convention, letters from both himself and his wife to his sister over a 20-year period suggest an affectionate relationship between the three of them and a happy family life. It is this that makes his unexplained departure even more shocking.

I often wonder whether Alice’s illness was a contributing factor to his leaving. Later medical records suggest that she was already suffering from epilepsy around this time. Attitudes to epilepsy and the impact of the condition on Alice herself, with the very limited treatment available, may have been more than he could cope with. It does seem that in later life he suffered from “melancholia” (a contributing cause to his death 15 years later) so it is possible that his own mental health made it harder for him to accept Alice’s illness.

Whatever the reason, William left his wife, and four children, when Alice was just 17 and Harry still a boy. The impact of this both emotionally and financially must have been enormous. It seems to have sent shock waves through the family, with William’s sister changing her will shortly afterwards to provide for Mary and her children. The only income the family would have had at this time would have been that earned by John and Bessie who were both teachers, but both were young adults who were planning their own independent lives.

In 1888, Bessie, the eldest daughter, married Harry Carver, a clerk at the time but with political ambitions, who later became Mayor of Leicester. My great-grandfather John had already moved from Leicester to become Headmaster of a school in Weston-Super-Mare. In the summer of 1889 he returned briefly to marry his Leicestershire bride, with their first son born in January 1890.

The 1891 Census shows Bessie, her husband and baby girl living three doors away from her mother, sister and younger brother. John is visiting his mother’s family (his own family are still in Weston-super-Mare). Neither Mary or Alice is working, so the only breadwinner in the household is 15 year-old Harry, working as a warehouseman. The household also includes a nurse, possibly helping to care for Alice, but more likely for her mother. When we consider the census alongside the gravestone, the reason for John’s visit home becomes clear. His mother Mary was ill and died less than two weeks after the census was taken, leaving Alice and 15-year-old Harry alone.

The loss of her mother must have been a huge blow to 22-year-old Alice. It was Mary who had cared for her through the seizures and the resulting injuries; Mary who had protected her from the condemning eye of a society that did not understand her condition; Mary who had kept her at home and out of institutions. Mary had been her mother, protector and carer and, without her, Alice was lost. Her asylum admission records suggest that her mental illness started at this point: depression brought on by grief, expressed through angry outbursts. Today we would recognise this as completely natural and offer support and counselling. Sadly in Victorian England it was seen as the beginning of mania and lunacy.

Neither of her older siblings offered her a home. Both were relatively newly married with small children so perhaps the prospect of caring for their increasingly ill, and possibly violent, sister was too much to contemplate. Her younger brother was not much more than a boy himself and soon left Leicester to make his own life in the army. Alice was “farmed out”: boarded on farms with strangers paid to take care of her, “care” that is likely to have included physical restraint and containment.

It seems that this was the final straw for Alice. Not only was she dealing with her grief at losing her mother and carer, but she was suddenly cast alone in a world that must’ve been frightening and confusing, particularly when she was dealing with recurrent seizures and their aftermath. We don’t know anything about the people with whom she stayed, but she was finally committed to the asylum in 1893 after “threatening those she lived with with a knife”, believing them to be going to harm her. Whether this was entirely the delusions of a young woman suffering a breakdown, as the doctors at the asylum concluded, or whether she had indeed been mistreated in some way and was responding out of fear and confusion, we will never know. We do know she arrived at the asylum with bruises on her arms, knees and thighs, and with a black eye, injuries that could have been sustained during seizures or as a result of assault.

Fielding Johnson Building at University of Leicester – previously the Leicestershire and Rutland Lunatic Asylum. ![Creative Commons Licence [Some Rights Reserved]](https://i0.wp.com/creativecommons.org/images/public/somerights20.gif) © Copyright Ashley Dace and

© Copyright Ashley Dace and

licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

Her case notes from 14 years in the asylum survive. The early entries depict a young woman suffering from severe seizures with increasing frequency, damaged mentally and intellectually by repeated fits, struggling to manage her depression, anger and frustration, but still aware of the struggle. She spends these early days walking outside, doing needlework or – on bad days – in bed. She is often tearful and distressed. One entry describes how she tries to throw herself in the fountain; another how she fights physically with other patients. She injures herself frequently in her seizures, hitting her head and biting her lip, the latter so badly that later she had to have a large section of her lower lip removed, adding facial disfigurement and, presumably, difficulty with eating and drinking to her other problems.

The Leicestershire and Rutland Asylum was significantly overcrowded by 1893. Plans were in place for a new, larger building but it was not ready for occupancy until 1908. In the Leicestershire asylum she would have shared a ward with at least 30 other women, quite possibly other epileptics and patients with suicide risk – all those considered in danger of injuring themselves were kept together where they could be watched. She would have had no privacy and little freedom of choice. The wards were designed as rooms off a central corridor, which also served as a day area. There was an outside exercise court, a library and a chapel. Patients were encouraged to work, in the laundry or the kitchen, or on the farm, though there is no evidence that Alice did so, possibly because of the risks from her repeated seizures.

Her epilepsy was treated with Bromide and Borax, the treatment of choice at that time, but both are toxic substances. Bromide has since been linked to side effects such as lethargy, reduced mental function and even psychosis. Combined with the damage to her brain caused by continuous and severe seizures, it is hardly surprising that her mental condition deteriorated. Later entries are depressing in their repetitiveness. She is described as irritable and awkward, slow to respond, unoccupied and fitting with ever increasing frequency, until her seizures are happening nearly every day. The tone of these reports is very unsympathetic: no recognition of her illness, the impact of the drugs she was taking or the traumas she had experienced. She was simply viewed as an awkward and lazy inmate.

The records for her final years in the asylum are missing, perhaps mercifully. In 1908 she would have moved from the buildings she had grown accustomed to, to the newly built asylum. I can imagine that this too added to her confusion, moved from an environment that she knew, to having to get used to a new ward and possibly new companions.

Alice died of the effect of epilepsy in February 1912, after 19 years in the asylum. We have no record of her having visitors over this period but her sister Bessie is given as her next of kin, and I like to believe that her older sister visited her on occasion; possibly her brothers too, when they returned to Leicester.

What we do know is that in death they took care of their sister. Alice finally left the asylum and was laid to rest in the family plot beside the mother who had looked after her and whose loss had had such a devastating impact on her life.

Janet, what a gripping story about Alice. The mystery surrounding her, the fascinating details of her family and surroundings, and the vivid details of her tragic demise had me glued to my seat. You crafted this story so well. I look forward to reading more. Isn’t this FHWC fun?

Thanks Linda. I’m glad you enjoyed it. I’m loving the FHWC – without it I wouldn’t have got round to any of this – and there are so many stories that deserve to be told.

Welcome to Geneabloggers! I wish you great success with your new blog 🙂

Michele

Thank you Michele – much appreciated. I am hoping that the prompts and community at Geneabloggers will keep me spurred on with this – so many stories to write up!

What a fabulous story, sad but good. It held me from the beginning and I had no idea how long it was until I finished reading! Welcome to the world of blogging.

Glad it held your attention! It is hard to keep the stories short enough when there is so much material – but good to know it didn’t feel too long.

Janet, what a tragic story! In one way, though, it is a consolation that her memory has been brought back to life in this small way through your documentation here.

Have you ever traced the route of Alice’s father? I’d be curious to see what became of him. I’ve been researching one Scottish man, an artist who left his family and, like William, emigrated to America. From my point of view, looking at current data I’ve found here and tracing my way back to his country of origin, it seems fairly easy. To research his trail in the opposite direction may be more challenging, but might provide some answers to those unspoken questions.

I found a mention of your blog today, thanks to GeneaBloggers. What really caught my eye was the mention of how you’ve not done much research on Welsh ancestors, though you currently live right there! I have a Welsh heritage, but it’s funny: I haven’t researched my own Welsh line, either. Perhaps it’s because I’d need to pick up the trail in the early 1700s…

Very sad that there was so much misunderstanding then isn’t it?

I have traced Alice’s father William to his death in Chicago in 1901 – he died in rather sorry circumstances it seems – his story is for another time.

On the Welsh roots – I don’t actually have any! I have ended up living here but sadly have no family connection – except that my brother-in-law was born here so I have done some research on his family. Where is your Welsh line from? I might be able to help….

Pingback: The end of the challenge | Finding Family

Such a sad story. Society seems to have been so slow responding to mental illness. It is also very curious as to why the father left. Do you know where he went to?

He ended up in Chicago. The 1900 census has him living there and he died in a charitable home a year later. The death certificate is ambiguous but there is a possibility that he committed suicide. He died a pauper.

He may not have gone straight to Chicago from England of course. I haven’t found anything for the period 1885-1900 – no passenger records, no census records. Brick wall so far..

What a touching and sad story. It is great that you were able to locate much of her actual case notes.

Regards,

Theresa (Tangled Trees)

Thank you Theresa. The case notes for this particular asylum are surprisingly in tact, to the extent that someone has written a history of the institution based on them. A shame that neither the photograph nor the final years for Alice have survived but I am still very lucky to have found so much.

Very well expressed and some fine research you have done here Janet. My father is the “Douglas” mentioned in first paragraph. The “Aunt Alice” that my father remembers meeting in Cairo was undoubtedly his mother’s sister, Alice Baxter (nee Kirkwell) who died in Cairo 1914.

John Brodie

John – good to hear from you. Yes indeed I’m sure you are right about it being your father’s mother’s sister that he met in Egypt. It was fascinating researching Alice’s story. I have neglected this blog badly however – I really must finish Henrietta Campbell’s story as well!

Hi. Came across your story by chance. I have just completed a biographical account of General John Oldfield who married first wife Mary Arden. None of this is mentioned in the copious notes on the Oldfield family of which I am a descendant. I read on another genealogical site that Colonel John Oldfield adopted Mary Arden Wise (Oldfield) in 1834 in Ireland, where John Oldfield was stationed at the time. Thus it seems that Mary may have been connected to the Ardens. The other piece of interest is the Buchan name. My GGGrandfather married Sophia Buchan, daughter of Captain David Buchan, who’s biography I have also published. It seems that I may have to do another edition of my books!

Can you supply any information on Alice’s mother – Mary, and what led to her being adopted.

Would love to know more.

John

I don’t know much about Alice’s mother, I’m afraid. According to her gravestone she was born on 13th January 1834, in Ireland according to census data, but I have no information about her mother. The first specific documentary evidence I have is her marriage to John Wise, a 22 year old sergeant, at the age of 16 in Bombay in 1850. Here she is given as Mary Holdfield (with her father given as John Holdfield) but I suspect this is an error, as on all other documentation it is Oldfield. John Wise died 5 years later in Bombay leaving her a widow at the age of 21. She then married William John Brodie, also a sergeant, in Bombay in 1856, and went on to have 5 children (4 surviving to adulthood including my ancestor John Buchan Brodie). The Buchan is an old family name – William’s father was also John Buchan Brodie – but I am not sure where the connection to Buchan starts.

The Arden connection and adoption is interesting and worth pursuing. Do you know where in Ireland the Oldfields lived? It would make it easier to explore who Mary may have been.

Hi Janet

John Oldfield married Mary Arden 1810. She died 1822. He then remarried Alicia Hume. John had two appointments in Ireland, during which he would have been stationed at Athlone. These were 1824-1829 and 1848-’54, during the latter period, in command of the Royal Engineers.

Claire Brodie on http://www.wikitree.com/genealogy/ OLDFIELD, mentions the adoption of Mary by John Oldfield. Do you have any documentary proof of this?

Times don’t seem to fit, but the full name Mary Arden Brodie is very suggestive!

Hi John – all I know for sure is that Mary’s father was a John Oldfield (from her marriage certificates) and that she was born in Ireland. I have no evidence that she was adopted. She was in India with the army in 1850 when she was still a minor so it is probably reasonable to assume her father was in the army but I have nothing more than that – he could be your John Oldfield or some other John Oldfield. In many ways – since she married a non-commissioned officer at such a young age – it is perhaps less likely that her father was a high ranking officer?

The first I had heard of Arden was your comment. I have never seen her referred to as Mary Arden Brodie before. I’ll get onto Claire and see if she has unearthed anything concrete to support this! But your information about John is very helpful because you are right – the dates are not promising. But it does give a place to look for a birth record for her in case there is a connection.

Thanks Janet.

Please keep me informed of any developments.

I suggest that a productive line of enquiry may be Colonel John Rawdon Oldfield. He was General John’s first son, and spent his army career in India, especially Peshawar from 1827 till his marriage to Jane Arden, his cousin, in 1846. He was the Adjutant of the College of Roorkee, where new engineers were stationed on arrival in India. He was a noted philanthropist, working with the Earl of Shaftsbury in his social efforts, especially the sending of ‘gutter children’ to Canada, New Zealand, etc. He was a trustee of the Home of Peckham, which was a home for orphaned girls in England.

There may be a real life story here.

Thanks again. I will definitely let you know if I find out anything more. Thanks for the pointers.

Hi Janet

I’ve had time to read the story of how you came about writing the story of Alice. You mention the name Henrietta Campbell. It may be just coincidence but the above John Rawdon Oldfield when he died in 1883, left some of his large estate to the two Miss Campbell’s of whom I know absolutely zero!

I note that Claire Brodie has changed the information on Wiki tree to John R Oldfield. Hopefully based on more than my suggestion???. I have not had any reply from her.

I suspect coincidence. Henrietta was the mixed-race wife of Dr David Shaw of Jamaica and the grandmother of Mary Oldfield’s second husband William John Brodie. As far as we know she never left Jamaica and although “Campbell” was passed down the generations of our family as a second name (my own grandmother was Margaret Evelyn Campbell Brodie) I am not aware of any other Campbell relatives. I suspect (but have no evidence) that Henrietta was the illegitimate daughter of one of the many Campbells living in Jamaica at that time – but I think a family connection to the Oldfields half a century after her death is unlikely.

I asked Claire and she hasn’t yet found any firm evidence of a connection with John R Oldfield – but she felt it was more likely than his father. I am going to see if I can find out how many John Oldfields were serving in Bombay in 1850 – it seems likely Mary was there with her family when she married John Wise given she was a minor. That might give us something to go on. It would be great to find a connection to your Oldfields but as yet there is nothing concrete.

Just checked my research from National Archives/British Library on John Wise (Mary’s first husband). He was a Sergeant in the 83rd Regiment of Foot (Dublin), based in Poona in 1850 at the time of his marriage. He died a Quartermaster Sergeant on 11th July 1855 at the age of 27 and was buried in Deesa. Mary had just turned 16 a month before their marriage so I suspect she must’ve been in India with her father. Is it a reasonable assumption that he would’ve been in the same regiment?